Most internal promotions don’t get this much attention. Most job selection processes don’t have centuries of history behind them — and few, if any, have a special name.

But then, most job selections don’t end with a new pope.

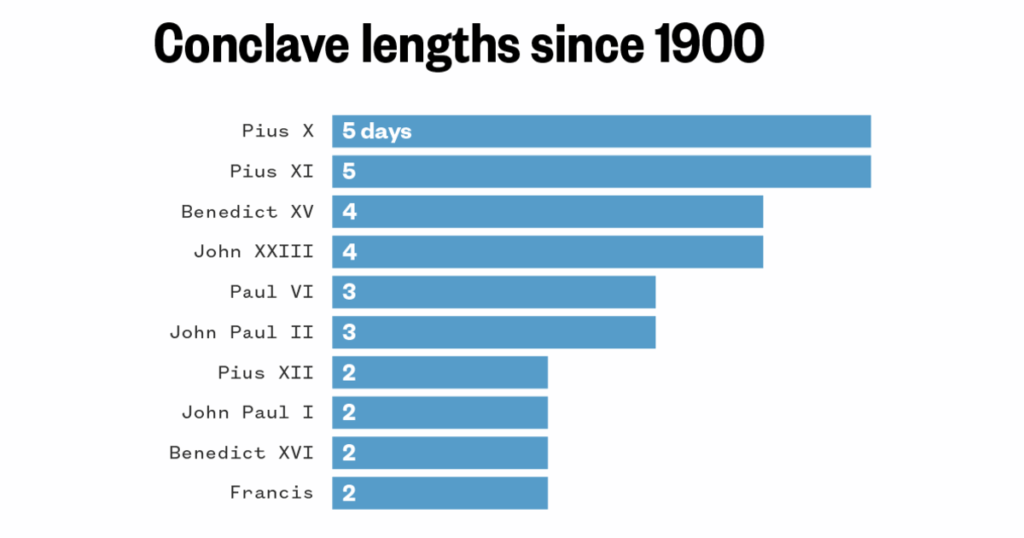

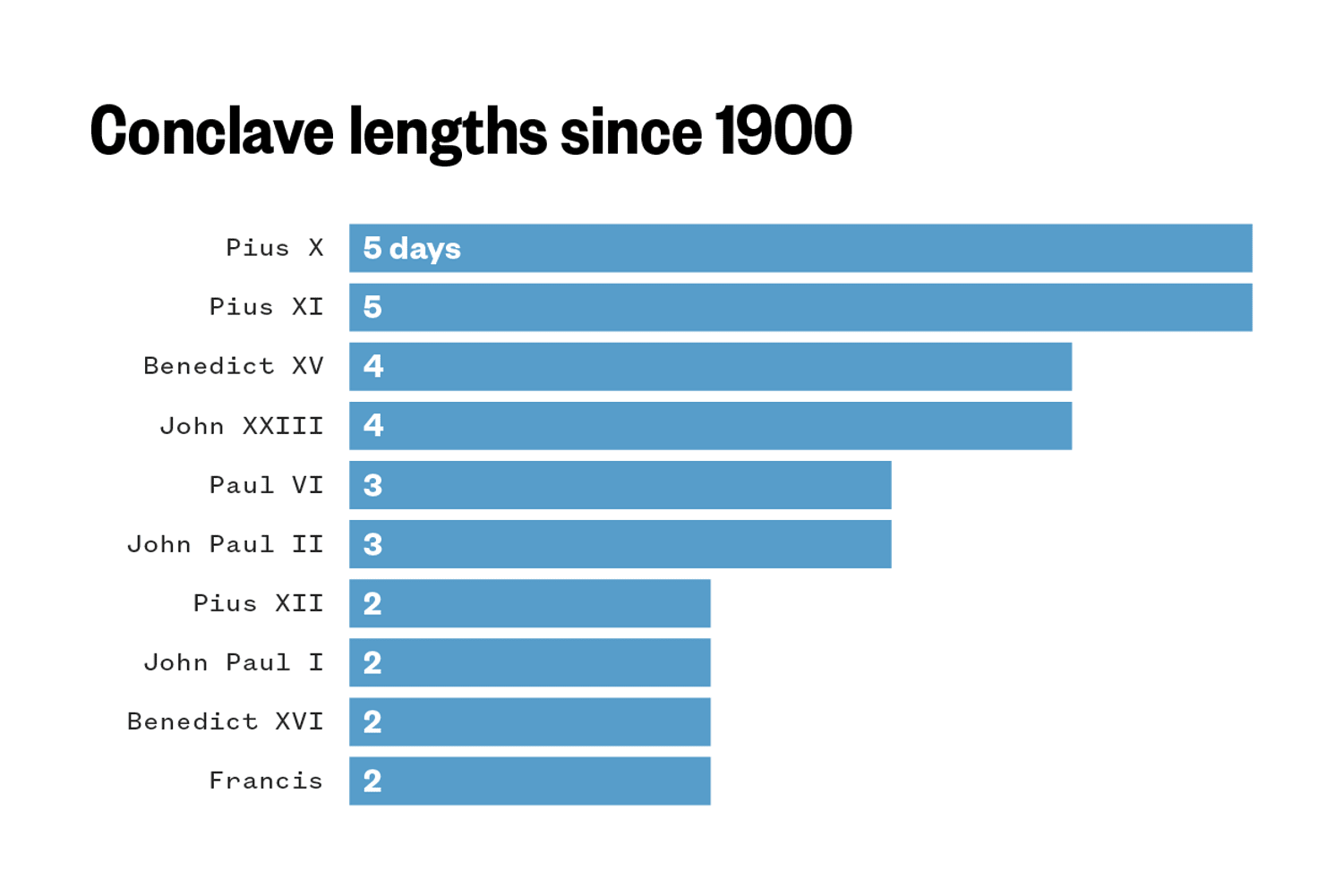

Catholic cardinals from around the world have converged on Vatican City for the conclave that will elect the successor to Pope Francis. The first day of of voting didn’t result in a pope, but if the pattern of the recent past holds, it won’t be long before one is announced. Data shows that conclaves don’t take as long as they used to.

Conclaves were first used to elect a pope about eight centuries ago, with early elections lasting months, even years.

It’s been nearly 200 years since a conclave took longer than a week, with modern conclaves typically taking two to three days.

The longest conclave of the past 200 years happened in 1831, when it took 51 days to elect Pope Gregory XVI.

The longest took place in the 13th century, before conclaves were formalized, when the process that eventually elected Pope Gregory X started in 1268 and ended in 1271. In all, it took two years and nine months, a process that led to the rules and procedures of conclaves.

Most popes choose their papal name upon election, a practice that’s been common for the past thousand years. For instance, Argentine Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio chose the name Francis upon being elected in 2013 — the first pope to use the name Francis. By comparison, there have been more than 20 popes with the most common name: John.

At the time of his death, Francis was the second-oldest pope in the last 400-some years.

Since 1600, more than 30 popes have served. Nine of those, including Francis, were 70 years of age or older when elected. And more than half worked into their 80s — something that’s happening more and more as the average age of popes climbs.

Latest World Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest World Breaking News Online News Portal