WASHINGTON — A case that could weaken the separation of church and state goes before the Supreme Court on Wednesday as the justices consider whether Oklahoma can approve the first-ever religious public charter school.

Although the oral argument concerns only St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School, which would operate online throughout the state with a remit to promote the Catholic faith, the case could have broad ramifications.

The dispute, which pits Republicans in Oklahoma against each other, highlights tensions within the Constitution’s First Amendment. While the Establishment Clause prohibits state endorsement of religion or preference for one religion over another, the Free Exercise Clause outlaws religious discrimination.

Lawyers for St. Isidore, who are defending the proposal along with the Oklahoma Statewide Charter School Board, have a narrow interpretation of the Establishment Clause and say barring religious entities from applying to run charter schools would run afoul of the Free Exercise Clause.

The Archdiocese of Oklahoma City and the Diocese of Tulsa jointly proposed the school.

“It’s not establishing a religion. It’s the government realizing that there are benefits to having private entities, and we just happen to be a religious private entity providing a valuable service,” Michael Scaperlanda, a former law professor who is now chancellor of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City, said in an interview.

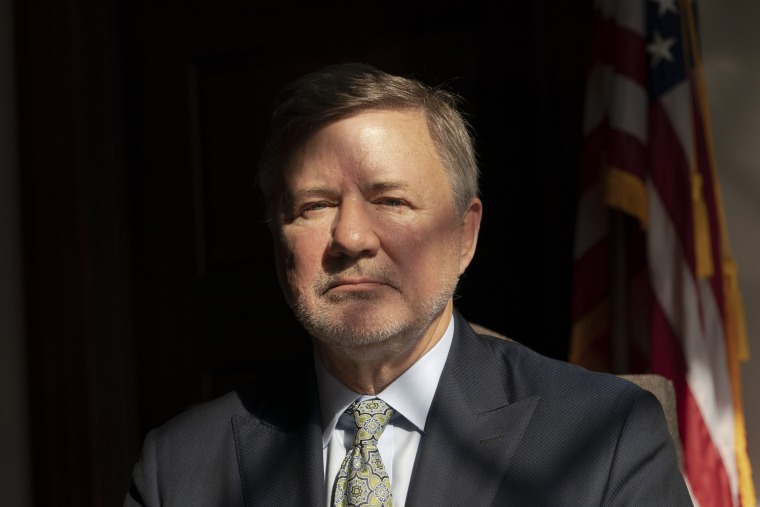

Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond, a Republican who challenged the decision to approve the school, said that although supporters of the idea are pushing a religious liberty narrative, he sees it differently.

“It is what it is, and that’s religious indoctrination,” he said.

In recent years, the Supreme Court has repeatedly strengthened the Free Exercise Clause in cases brought by conservative religious liberty activists, sometimes at the expense of the Establishment Clause. Some conservatives have long complained that the common understanding that the Establishment Clause requires strict separation of church and state is flawed.

The case raises two legal questions. The first is whether charter schools are public schools that are effectively instruments of the state or entirely private bodies that just happen to receive state funding.

If they are “state actors” in legal terms, then the state, wary of violating the Establishment Clause, is free to require that charter schools be secular.

The second question is, assuming charter schools are private entities, whether it is a form of religious discrimination under the Free Exercise Clause to bar religious schools from a state charter school program that other entities can participate in.

Although the court has a 6-3 conservative majority that often backs religious rights, the case is complicated somewhat by conservative Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s decision to recuse herself. Were the court to split 4-4, the Oklahoma Supreme Court ruling that said the school was unconstitutional would remain intact.

Barrett did not explain why she stepped aside. Before she become a judge, she was a professor at Notre Dame Law School and has close ties there. The law school’s Religious Liberty Clinic represents St. Isidore.

The campaign to authorize religious public charter schools dovetails with the school choice movement, which supports parents’ being able to use taxpayer funds to send their children to private school. Public school advocates see both as broad assaults on traditional public schools.

The school’s lawyers present the case as strictly a Free Exercise Clause issue and cite to a trio of recent rulings in which the Supreme Court said states cannot bar religious entities from programs that nonreligious private groups can apply for.

“Yet, that is precisely what the state did here,” they wrote in court papers.

Drummond countered in his own briefing that charter schools in Oklahoma are like all other public schools, meaning the state can require them not to be sectarian.

How the court ultimately rules will have nationwide implications. All 46 states that allow public charter schools do not allow religious entities to participate, so a ruling in favor of St. Isidore would open the doors to other states’ either changing their laws to allow religious schools or facing lawsuits that would require them.

Drummond said in court papers that such a ruling would bring charter school laws nationwide into question and give “special status” to religious charter schools, because, unlike secular schools, they may not have to comply with certain laws that apply to charter schools if they conflict with religious beliefs.

He told NBC News, “If we go down this road, we have to be prepared for the ramifications.”

A win for St. Isidore could also have unintended consequences, lawyers for the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools warned in a friend-of-the-court brief. They noted, for example, that many charter schools would risk losing vital state funding if the court concluded they are not public schools given that the state bans public money going to any private schools, whether they are religious or not.

The case could also have repercussions at the federal level, where a program that provides funds to charter schools prohibits money from going to sectarian schools.

A state board approved the proposal for St. Isidore in June 2023 despite concerns about its religious nature.

Drummond immediately took legal action, asking the state Supreme Court to intervene and declare the plan unlawful.

The state court ruled last year that the school would violate both state law and the First Amendment.

Latest World Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest World Breaking News Online News Portal