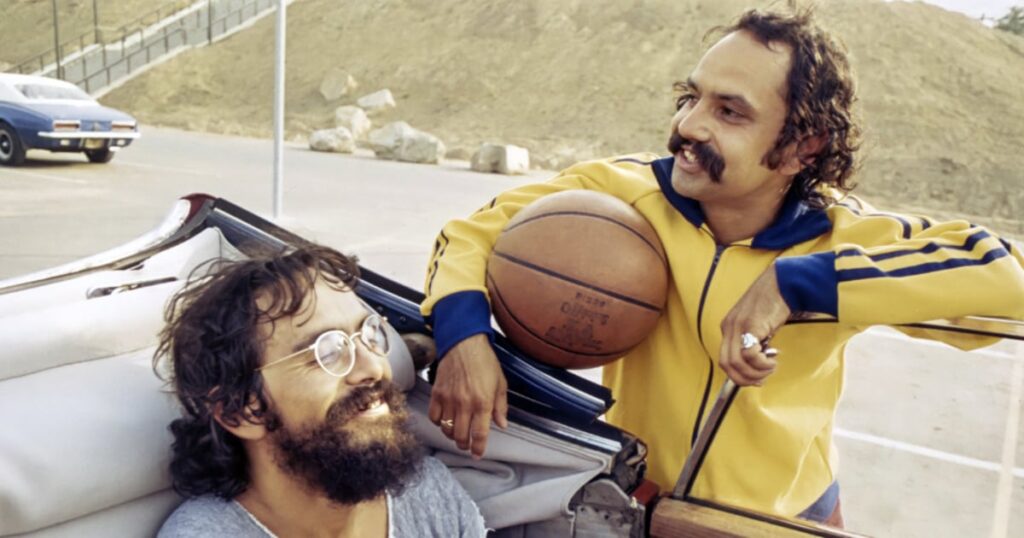

It was almost half a century ago that Cheech Marin and Tommy Chong teamed up for the first time on screen and told a lighthearted story about two pot-smoking buddies on a road trip.

Over time, the 1978 movie “Up in Smoke” became a cult classic that transformed the two comedians and actors from hippie outsiders to comedy icons.

Now, longtime Cheech and Chong fans or those who want to know more about them can see Marin and Chong reunite on screen in “Cheech & Chong’s Last Movie,” released nationwide Friday. Directed by David Bushell, the documentary weaves never-before-seen footage from Marin and Chong as the two take another road trip — this time spanning five decades of their ultimately widely successful careers spanning platinum albums and box-office fame.

“They found the essence of Cheech and Chong. And that itself is worth exploring, because there’s a Cheech and Chong in everybody,” Chong said about the documentary in a joint video interview with Marin. “That’s who we are; we’re everybody out there. And that’s why people can relate to us.”

For many fans today, stoner comedy invites them into playful spaces that use humor to blur or soften social boundaries. “Up in Smoke” helped create and popularize a subgenre of later hits like “Fast Times at Ridgemont High,” “Friday,” “Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle” and “Pineapple Express,” among many others.

But when it first came out, Cheech and Chong’s “Up in Smoke” was certainly not a hit with everyone.

“Any film that asks you to go smashed before you see it must have something really bad to hide,” the late Chicago-based film critic Gene Siskel said on his award-winning movie review TV show “Siskel & Ebert.”

Siskel picked “Up in Smoke” as a “Dog of the Week” — his choice for worst film — and criticized its dialogue, saying it was “80 minutes of two jerks saying nothing but ‘hey man.’”

Yet those two casual words, “hey man,” would nevertheless resonate with many fans and signal a generational change in mainstream culture.

“In their sleepy, unshaven way, Cheech and Chong constitute a visual affront to the straight world just by walking down Main Street,” a 1978 New York Times review said. “It’s a revolution without danger, however, because, as the movie’s popularity shows, this particular revolution has already been won. The true eccentrics are no longer Cheech and Chong but the clean‐shaven nitwits, like the cops in ‘Up in Smoke,’ who persist in their attempts to uphold repressive traditions.”

Frederick Luis Aldama, a pop and Latino culture scholar who is the Jacob & Frances Sanger Mossiker Chair in the Humanities at the University of Texas, Austin, said in a phone interview that “if you really distill it, stoner comedy is a great equalizer. It puts the doormat out for everyone to generally enter that place. And it’s a reminder for a time and space where you can be yourself, let yourself go.”

Aldama remembers seeing “Up in Smoke” with his maternal “abuelita” (grandmother). He remembers her “laughing uproariously” throughout the film, which made him laugh, too.

It also gave him a sense of pride as a Latino, he said. Marin grew up in East Los Angeles, the son of Mexican American parents; his father was a World War II Navy veteran and a Los Angeles policeman. Chong grew up in Calgary, the son of a Canadian mother with Scottish and Irish roots and a Chinese father.

The comedians, Aldama said, brought elements such as Mexican American lowrider culture into the mainstream, for example, but “they did it in a way where you weren’t asked to judge or laugh at it, but simply enjoy it and laugh with it. And this put a positive spotlight on our communities, our neighborhoods.”

Marin’s and Chong’s childhoods were separated by more than 1,500 miles, and different circumstances would ultimately bring them together in an unexpected way.

Marin dodged the Vietnam War by moving to Canada. And Chong, who had been a guitarist for Bobby Taylor & the Vancouvers, said he lost his job in Motown.

“I was just trying to get my life back together. And Cheech was trying to live with the fact that he had to live in Canada. And then we met,” said Chong, 86. “We realized that we had this understanding.”

The seed for their understanding was planted at a Vancouver topless nightclub where Chong was a part-owner and had formed a hippie-burlesque comedy troupe. Marin would join the group as a writer. And then, the duo continued to develop their stoner act even after the troupe folded.

After years of success, the two went their own ways, and they have some frank discussions in the documentary about their relationship.

Asked whether comedy could still be transgressive, Marin says it can, as long as there is an authentic connection between the comedian and the audience.

“It depends upon the right comedy and if it’s truthful comedy. It’s not the comedy that wants to please everybody. We want to please ourselves. And in doing so, [we] do something that’s relevant for the people,” said Marin, who’s 78. “I think that will keep happening, absolutely.”

But for comedy to succeed today, Chong said, it can’t simply repeat what was done in the past.

“We’re living, like, in a travelogue,” he said. “We’re no longer in the ’60s, the ’70s or the ’80s or the ’90s. We’re now. And so, in order to stay relevant, you got to acknowledge what’s going on now. Because we’re alive and we’re still breathing, we can still think about it.”

Asked whether this was really their “last” movie and what would get them together on screen again, Marin said, “Very easy, money!”

“No, we’re going to keep hammering until they take the cold, warm bong out of my hand,” Chong said, as the two men laughed.

Latest World Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest World Breaking News Online News Portal