Several district attorneys have considered charging former death row prisoners whose sentences were commuted by former President Joe Biden months after a White House executive order called on them to do so.

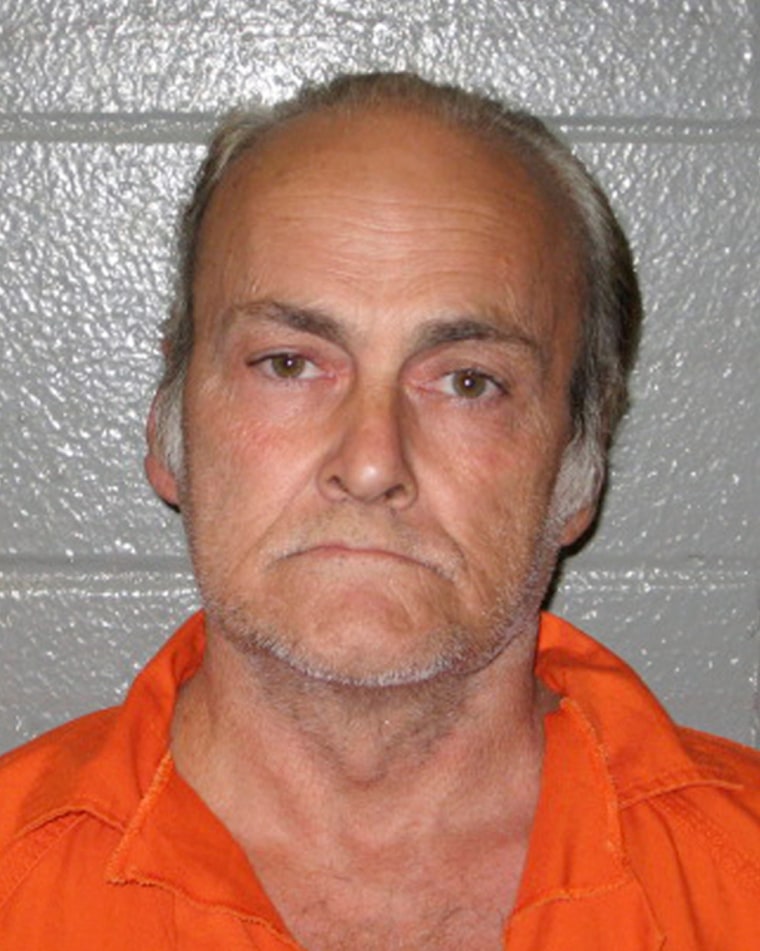

So far, a Louisiana prosecutor successfully sought a first-degree murder charge against Thomas Steven Sanders in the death of a 12-year-old girl who was killed in Catahoula Parish in 2010. While Sanders’ federal death sentence was commuted to life without parole by Biden’s order just a few months ago, a Louisiana jury could reimpose a death sentence on him under state law if he’s found guilty.

Catahoula Parish prosecutor Brad Burget did not respond to requests for comment about the grand jury’s indictment two weeks ago, but told NBC affiliate KALB in Alexandria that he disagreed with Biden’s decision in December to grant clemency for those death row inmates.

“It just disrespects the victim,” he said.

Burget’s decision comes after President Donald Trump issued an executive order on the death penalty that both broadly declared that the U.S. should “ensure that the laws that authorize capital punishment are respected and faithfully implemented,” and also took specific aim at “each of the 37 murderers whose Federal death sentences were commuted by President Biden.”

Trump’s order specifically calls on the U.S. attorney general to take two specific actions related to those recently resentenced inmates: to “ensure that these offenders are imprisoned in conditions consistent with the monstrosity of their crimes and the threats they pose,” and secondly, to “further evaluate whether these offenders can be charged with State capital crimes and shall recommend appropriate action to state and local authorities.”

NBC News has learned that several other district attorneys have considered weighing charges against these former death row prisoners after contacting prosecutors’ offices in seven other cases.

The prosecutor in Horry County, South Carolina, has two separate cases involving the recently commuted death row inmates: one involving Brandon Basham and Chadrick Fulks, whose 2002 crime spree included the abduction and murder of a 44-year-old woman in Conway, and another involving Brandon Council, who was convicted of the murders of two bank employees in Conway in 2017.

“We have not made any decisions on those cases yet,” 15th Circuit Solicitor Jimmy Richardson said. “We have met with the families and are in the process of reviewing the evidence, but no decisions have been made.”

South Carolina only began resuming executions in September after a 13-year pause, and for the first time last month, put a condemned inmate to death by firing squad.

Meanwhile, two other district attorneys’ offices confirmed they have similarly reviewed their cases involving death row inmates whose sentences were commuted by Biden. It’s unclear whether Trump’s order prompted the reviews.

The St. Louis Circuit Attorney’s Office in Missouri said it had evaluated the case of Billie Allen and Norris Holder, who were convicted in separate federal trials in the death of a security guard during an armed bank robbery in 1997.

With both men now serving federal life sentences without the possibility of parole, “additional charges at the state level would not enhance public safety in the St. Louis region,” the attorney’s office said in a statement, adding further prosecution “is not in the public interest.”

The Tarrant County District Attorney’s Office in Texas said it had also looked into the case of a former federal death row inmate, Julius Robinson, who was convicted in 2002 in the killing of three men in drug-related incidents.

“We have discussed the facts and circumstances of Julius Robinson’s case with both former and current federal prosecutors familiar with the case. This case is not viable for a capital murder prosecution in Tarrant County,” prosecutors said in a statement, without elaborating further.

Bringing state charges in cases that were already federally prosecuted — and vice versa — is not uncommon, experts say, but doing so in an effort to reinstate death sentences may be complicated if not impossible.

For 15 of the 37 former federal death row inmates, their crimes occurred in states that either abolished the death penalty, such as Illinois and Virginia, or have either formal or informal moratoriums on executions, such as California, North Carolina and Ohio.

Then, for 11 other inmates, the crimes for which they were sentenced to death transpired on federal lands, such as a national park or in a U.S. government-run prison.

In those cases, prosecutors could still attempt to bring charges as long as they show the state has jurisdiction as well, said Barry Wax, a Florida defense attorney.

In 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the long-standing idea that prosecuting someone for the same crime in state and federal courts doesn’t violate their protection against double jeopardy because states and the federal government are “separate sovereigns.”

“When a state looks to prosecute someone for murder that they’re already doing life in a federal penitentiary for, it’s a roll of the dice,” Wax said. “The only difference is if you can get a jury to agree on a death sentence, and that’s not guaranteed. Otherwise, is it worth going through all of that again?”

Louisiana defense lawyer Cecelia Kappel, an attorney for Jessie Hoffman Jr., who last month became the first inmate in the state to be executed by nitrogen gas, said it is “extremely unusual” that a prosecutor in Catahoula Parish would want to seek another trial in a case that had already won a conviction for federal prosecutors.

Kappel said the parish, which is rural and has fewer than 9,000 people, does not typically hold capital trials and doubted it has the necessary resources to put one on. Capital trials can be costly because of the need to house and feed jurors if they are sequestered and potential payment for expert witnesses and their travel expenses. In 2014, it reportedly cost DeSoto Parish, which has three times the population of Catahoula, $105,209 for one capital trial.

Kappel said there are other factors to consider in trying cases many years later, such as the availability of witnesses and evidence, as well as the defendants themselves, who may be older and in declining health. She added that another murder trial against Sanders, who is now 67, could take years to begin.

A federal defender in Sanders’ case did not respond to requests for comment.

“They’re playing games with taxpayer money and playing games with people’s lives,” Kappel said. “And especially playing with the state public defense system.”

Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill, who supports the death penalty, had thanked Burget, the local prosecutor, in a social media post for seeking an indictment against Sanders. Her spokesperson said in an email that the office “will offer any assistance they may need in handling this death penalty case, like the AG has offered to every other DA in our state.”

When asked for comment about Louisiana’s efforts, a Justice Department spokesman referred NBC News to a February memo issued by Attorney General Pam Bondi on her first day in office that says the federal Bureau of Prisons would ensure states “have sufficient supplies and resources to impose the death penalty.”

Since then, the Justice Department announced it would seek a death sentence against Luigi Mangione, the man suspected of killing UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson last year. Three others currently remain on federal death row.

Latest World Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest World Breaking News Online News Portal