The voice on the end of the phone is deceptively friendly. “Nice to speak to you again, Garry,” Stewart Copeland says, pausing a beat before adding, “I haven’t forgotten what you wrote about my band 48 years ago…” Ridiculous. It was 47 years. But who’s counting? Criticising The Police was like firing peanuts at a Panzer tank. The world-conquering trio Copeland formed in 1977 notched up five multi-platinum studio albums, 18 hit singles and five Number Ones – including Every Breath You Take, the most played song in radio history. Since then, square-jawed Stewart has written film scores, operas, and ballets. His latest album stars animals – actual wildlife, not badly behaved rock’n’rollers. He’s gone from De Do Do to De Do Dolittle.

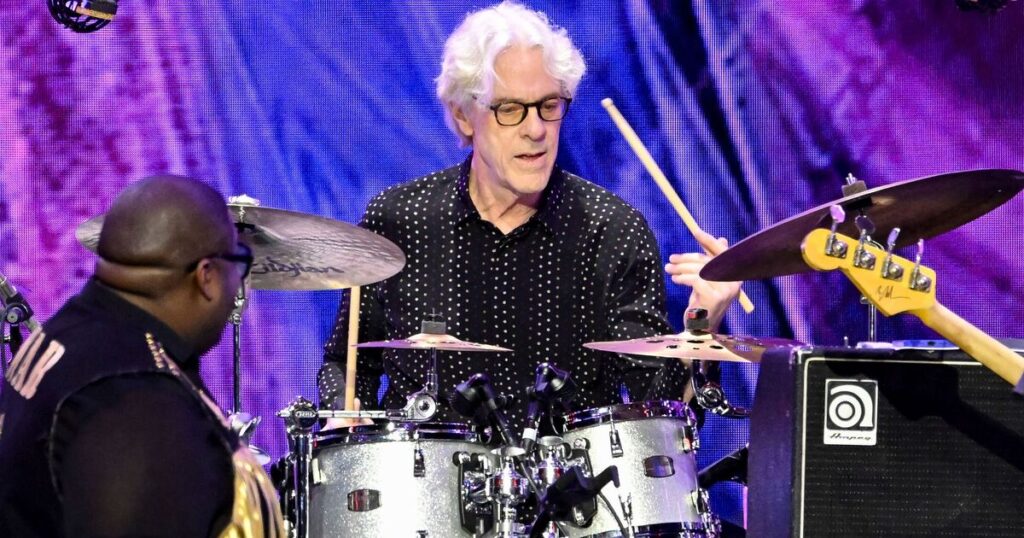

Stewart, 72, rated one of the world’s best drummers, has never lost his combative edge. An articulate enthusiast for free enterprise, he was one of the few 80s stars who dared to question the music industry’s left-wing orthodoxy, taking part in a 1986 debate for Melody Maker with Red Wedge – a pro-Labour pop star led campaign. “It was like taking candy from a baby,” he tells me. “I challenged Paul Weller on socialism, I asked him if he paid his crew as much as he paid the band.” As an ardent advocate for capitalism, Virginia-born Stewart is not sold on his tariff-crazed President. When I mention Trump’s name, he repeats “I shall not be triggered” seven times as a calming mantra.

Copeland and Sting never saw eye-to-eye on politics but he swears he only broke one of the singer’s ribs accidentally in a play-fight. There is less creative friction with his latest band mates who include an owl, a hyena, six croaking frogs, two wolves, and a white throated sparrow. His Wild Concerto album fuses his orchestral compositions with authentic animal sounds recorded in the field by The Listening Planet’s Martyn Stewart, nicknamed ‘The David Attenborough of Sound’. “I had the easy job. I built the music around these amazing noises – Martyn had to go out on his hands and knees, getting bitten by all-comers, to get them.” There’s atmospheric jungle-scape backdrop; rhythmic, repetitive bird calls, and melodic “divas, like white-throated sparrows; their singing isn’t strictly pitched, but the human brain creates a pitch, so when I put a flute next to a red-breasted nuthatch, the brain combines the two.”

Copeland’s first score for Francis Ford Coppola’s 1983 film Rumble Fish married music with street sounds, dogs barking, glass breaking, and traffic. He’s scored more than sixty since, including Oliver Stone’s Wall Street, but stopped twenty years ago. “Film studios and the rat race drove me nuts,” he says.

Stewart’s parents were Miles Copeland, a key US World War II intelligence officer who co-founded the CIA, and Aberdeen-born Lorraine, an archaeologist working for British Intelligence. The family moved to Cairo when he was two months old, then Beirut. At 14, they were evacuated to London. “I grew up there – I came from the wood…St John’s Wood,” he jokes. “I’m from the wrong side of the tracks – the Bakerloo line tracks. I’m more of a ‘teabag’ than you think.” Boarding at Millfield public school in Somerset on a scholarship, he says, “I was ‘the American’ and had to speak up for myself as an American. Then the accent was an affectation, now it’s real.” Unlike his British accents which he acknowledges “all sound like Dick Van Dyke now”.

Stewart was 12-years-old when his band the Black Knights first performed at the US Embassy beach club in Beirut, playing tracks by The Animals and James Brown’s I Feel Good. At their next show, at the British Embassy beach club, he noticed 15-year-old Janet. The attraction was instant but one-sided. He recalls, “She was completely out of my league – until I started banging the drums. She was dancing to a groove I was making. I was a scrawny kid, but behind the drums I was an 800-lb silverback.” His career path was set. At 22, Copeland joined faltering British prog rock band Curved Air, later marrying singer Sonja Kristina. “As I told Sonja, I was the last rat to jump onto a sinking ship, but we had a great time on tour, we always went down a storm.”

After they disbanded in late 1976, Stewart started putting The Police together. He replaced his first guitarist Henry Padovani with Andy Summers in August 1977 but still needed a bassist. Sonja reminded him of an amazing chap they’d seen in Newcastle jazz band, The Last Exit – Gordon Sumner, aka Sting. The Police’s punky debut single Fall Out was greeted with indifference in February 1977, and times were tough. Copeland was living off his savings from Curved Air, hiring amps and trucks for gigs. A Wrigley’s TV ad inspired The Police’s blond look. Booked as a wild rock star, Sting volunteered Andy and Stewart as the band. “To make us look wilder they peroxided and spiked up our hair. A cool look. The £50 they paid each of us kept us going for a month.”

Copeland had a minor hit with Don’t Care as Klark Kent in 1978, appeared on Top Of The Pops with Sting cavorting in a gorilla mask. “I’m glad you brought that up,” he says, grinning broadly. “Thanks to me, his first TV appearance was in a gorilla mask miming a bass line. I had the first laugh, but he got the last laugh – by writing all those hits for The Police.”

After signing to A&M, the trio broke through with Roxanne months later. Within five years they were headlining New York’s Shea Stadium, playing to 60,000 people. “It didn’t feel like five years, it seemed like a lifetime,” says Stewart. “Every little step was incremental.” They were booked to support Alberto Y Lost Trios Paranoias on a UK tour when Can’t Stand Losing You went Top 3. “The first night it was jammed. Their manager said ‘We should’ve charged you for this’, but they soon realised who the crowd had come for. We went out as a support act and all we heard was the shrill, high-pitched scream of teenage girls. If piranhas could make a sound, that’s what they’d sound like.” Their toughest gig was in America, when the Ramones opened for them. “They came out and just burnt it up. We were cold, tired, and hungry after seven hours of driving. We just couldn’t get it up that night.” An Italian show was delayed by a riot. “Our dressing room was underground and the tear gas still reached us; but we did go on stage eventually.”

The Police clocked off in 1984, not properly re-uniting until their 2007 Reunion Tour which grossed more than their entire previous income. “I take pride in the Police with those two mother-******s, I’m very proud of that. Opera is more obscure. I learned how to write operas from doing film work. There’s a synergy between music and drama. I love operatic singing. My wife Fiona says ‘Why are you writing opera? None of our friends like opera’. But opera houses are beautiful. It’s all about art. Their business model is to lose money.”

Copeland’s compositions range from concertos to 2021’s Grammy-winning new age album Divine Tides with Ricky Kej. If his music career had crashed, he’d have probably been a journalist – he had reviewed instruments for Sounds in the 70s. But writing advertising jingles was more lucrative. His Mountain Dew ads for the Super Bowl paid “six figures for 60 seconds”. BlackBerry paid him a fortune for a five-note earworm. “The pay for each note would have put my kid through private school for a year.” He has seven children, three with Fiona. What’s he like to live with? “I’m an interrupter – something my kids beat me up about all the time. The boys are older. They’re heard my jokes. I love my eldest daughter’s first boyfriend. He still laughs at them.” He’ll be performing his Wild Concerto in London on April 22 and is working on one final opera before finishing two ballets. He wants to conduct more, he’s writing a book, The Young Rock Star’s Handbook, and will bring his spoken word tour back here this Autumn. “Doing stuff keeps you fit. I still want to burn the house down,” he says. “I still want to bang s***!”

Stewart Copeland’s Wild Concerto is released on Friday April 18 on Platoon Records.

Latest World Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest World Breaking News Online News Portal