Phyllis Jones wakes up every morning to work up a sweat in countries all over the world, “and even sometimes on the moon,” she said, thanks to her favorite workout gadget, a virtual reality headset.

Her focus on exercise is light-years away from where Jones, 66, of Aurora, Illinois, was just a few years ago. She had prediabetes, and her cholesterol and blood pressure levels were inching up.

She was totally sedentary after falling into deep depression. “I was in bed. I didn’t care at all. I was just spiraling,” Jones said.

She was probably also destined to lose her ability to think clearly.

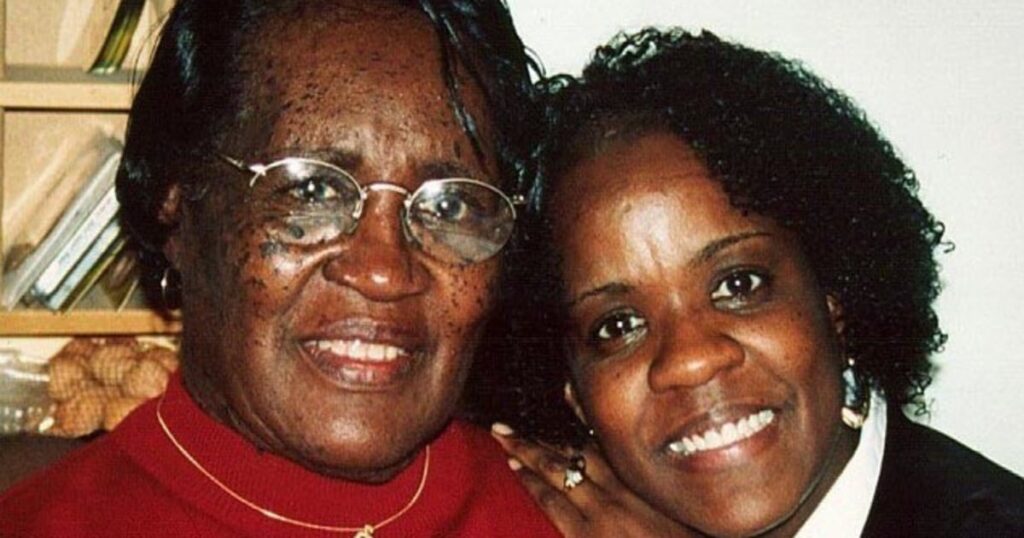

Jones’ mother and grandmother died of vascular dementia, a condition that occurs when the body can’t pump enough blood to the brain. Other family members had the disease, too.

“Watching two generations suffer made me determined to break the cycle for myself,” Jones said. “I’m not that person anymore.”

Four years ago, Jones joined a major clinical trial, called U.S. POINTER, that aimed to figure out how older adults at high risk for dementia can stay healthier longer.

Half of the more than 2,000 participants were given advice on a healthy lifestyle, including diet and exercise. The other half was thrust into a structured, team-based program that gave participants goals to transform their lifestyles. The program included meeting with experts and other participants regularly, as well as brain exercises and aerobics classes. Participants were instructed to follow the MIND diet, which trades processed foods for whole grains, fruits, leafy greens and other vegetables.

The researchers evaluated cognitive function by measuring memory, the ability to focus while juggling multiple tasks, and how quickly people interpreted and responded to information.

After two years, both groups showed progress. But people in the structured group saw greater benefits.

“Our conservative estimate shows that, relative to the self-guided group, the structured group performed at a level comparable to adults who were one to two years younger in age,” said Laura Baker, lead researcher and a gerontology professor at Wake Forest University School of Medicine and Advocate Health in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

“This is what’s giving folks additional resilience against cognitive decline,” she said.

Greater support and accountability in the structured group were key benefits.

“We’re going to tell you what to do, but we’re also going to help you get there, and we’re going to work with you as a partner to meet you where you are,” Baker said during a news briefing about the findings Monday at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in Toronto.

The research, published simultaneously in the Journal of the American Medical Association, is the first large-scale randomized controlled trial to show that organized, sustainable lifestyle interventions can have a measurable impact on brain health.

It’s an important finding as the nation is on a path to double the number of people living with dementia by 2060. About 10% of Americans over age 65 have been diagnosed with dementia, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nearly 7 million people in the U.S. have Alzheimer’s, the most common type of dementia.

While some drugs may slow how quickly dementia develops, there is no cure.

“Some people are scared, thinking there’s nothing you can do” to ward off dementia, said Dr. Richard Isaacson, a neurologist and researcher at the Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases in Florida.

We’re not powerless in the fight against cognitive decline.

Dr. Richard Isaacson

The new findings, he said, show that “we’re not powerless in the fight against cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease.” Isaacson, who formerly directed the Alzheimer’s Prevention Clinic at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, was not involved with the new research.

This isn’t the only study to link lifestyle to a delay in dementia.

Other research presented at the Alzheimer’s Association conference Monday found that regular walking can protect the brains of people with a genetic risk for Alzheimer’s.

The beauty of lifestyle interventions now proven to help keep cognition sharp is that they can be applied universally, said Rachel Wu, an associate professor of psychology who researches cognition in older adults at the University of California, Riverside.

“There’s no downside, no side effects to doing this stuff, except just the time it takes,” Wu said.

POINTER trial researchers also took blood samples and scanned participants’ brains, looking for amyloid and tau, proteins associated with Alzheimer’s disease that form plaques and tangles in the brain.

Those samples will be included in a future analysis of study participants, said Heather Snyder, a POINTER researcher and senior vice president of medical and scientific relations at the Alzheimer’s Association.

“If you have this biology, do you see a better response? Less response?” she said. “That’s the kind of meaningful question we’re going to be able to ask with this data.” Additional findings are expected within the year, Snyder said.

Jones is eager to see those results when they’re available.

“I don’t know what they saw in my brain, but I know I’m a different person,” Jones said. She’s lost 30 pounds and is no longer considered prediabetic or a candidate for statins to reduce her cholesterol.

“I’m going to keep moving, eating right, socializing, monitoring my comorbidities,” she said. “I’m going to take care of myself.”

Latest World Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest World Breaking News Online News Portal