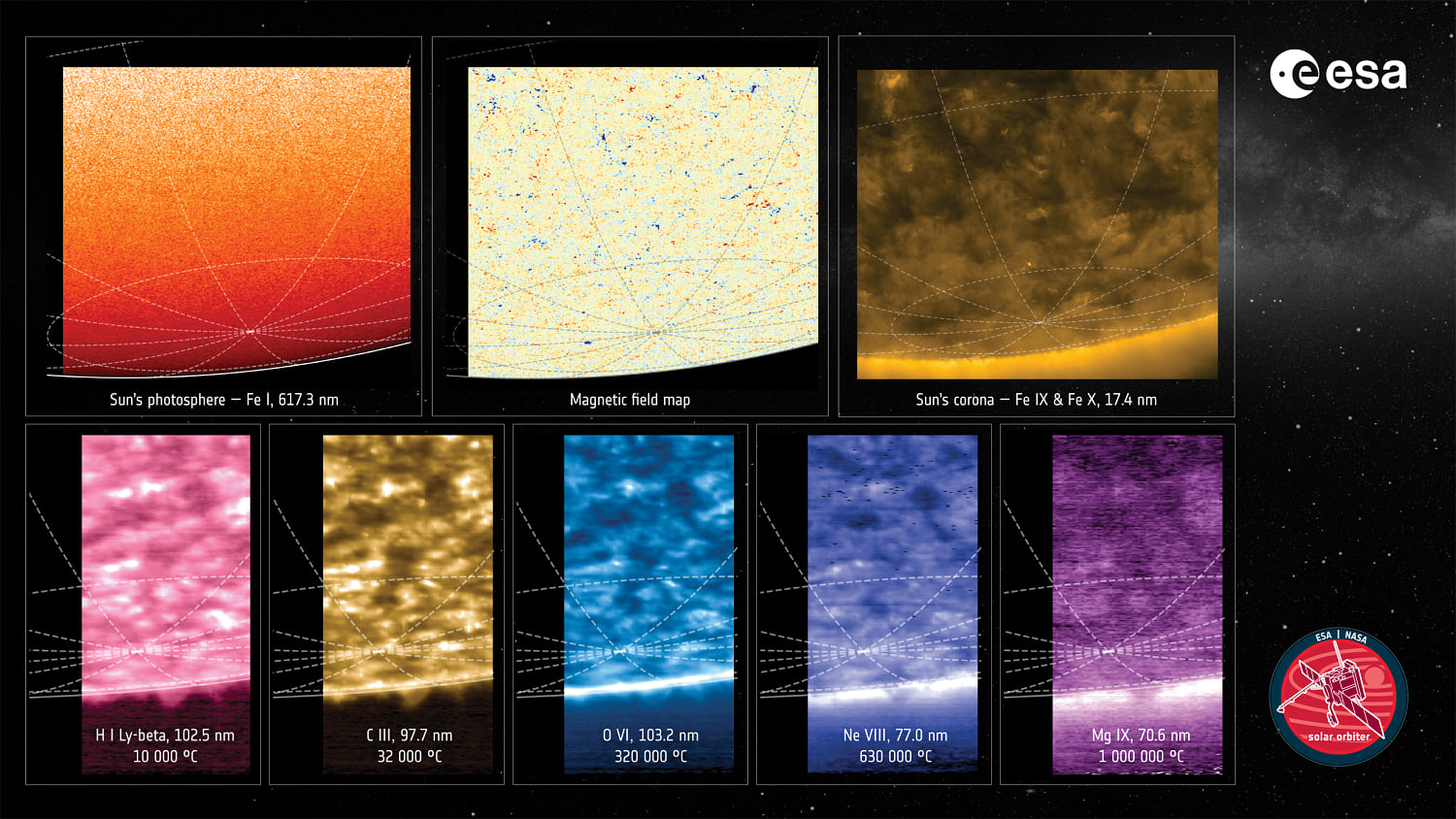

From the spacecraft’s observations, scientists discovered that magnetic fields with both north and south polarity are currently present at the sun’s south pole. This mishmash of magnetism is expected to last only a short time during the solar maximum before the magnetic field flips.

Once that happens, a single polarity should slowly build up over time at the poles as the sun heads toward its quiet solar minimum phase, according to ESA.

“How exactly this build-up occurs is still not fully understood, so Solar Orbiter has reached high latitudes at just the right time to follow the whole process from its unique and advantageous perspective,” said Sami Solanki, director of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany and lead scientist for Solar Orbiter’s PHI instrument, which is mapping the sun’s surface magnetic field.

Scientists have enjoyed close-up images of the sun before, but before now, they have all been captured from around the sun’s equator by spacecraft and observatories orbiting along a plane similar to Earth’s path around the sun.

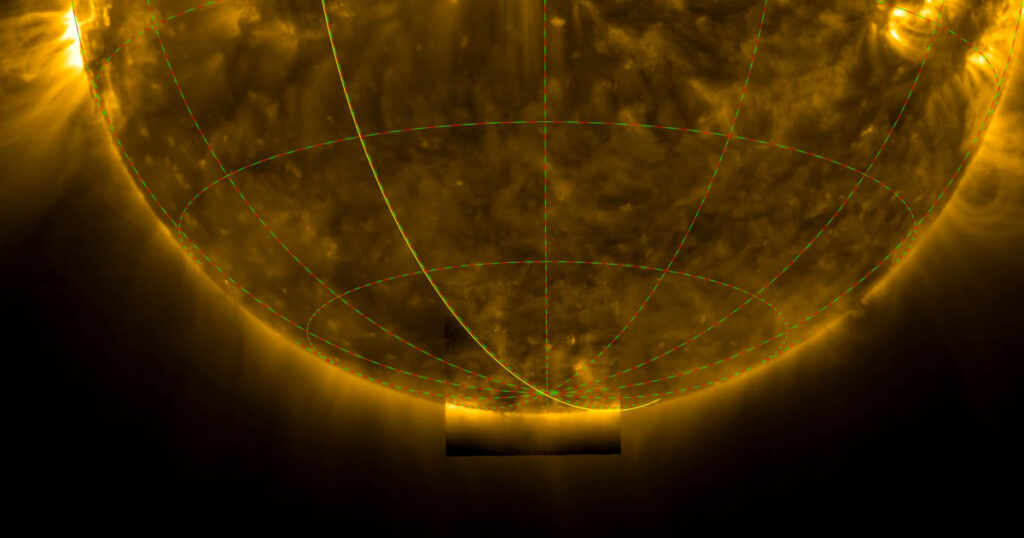

But Solar Orbiter’s journey through the cosmos included close flybys of Venus that helped tilt the spacecraft’s orbit, allowing it to see higher-than-normal latitudes on the sun.

The newly released images were taken in late March, when Solar Orbiter was 15 degrees below the sun’s equator, and then a few days later when it was 17 degrees below the equator — a high-enough angle for the probe to directly see the sun’s south pole.

“We didn’t know what exactly to expect from these first observations — the sun’s poles are literally terra incognita,” Solanki said in a statement.

Solar Orbiter was launched in February 2020. The European-led mission is being operated jointly with NASA.

In the coming years, Solar Orbiter’s path is expected to tilt even further, bringing even more of the sun’s south pole into direct view. As such, the best views may be yet to come, according to ESA.

“These data will transform our understanding of the sun’s magnetic field, the solar wind, and solar activity,” said Daniel Müller, ESA’s Solar Orbiter project scientist.

Latest World Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest World Breaking News Online News Portal